I tune my harp. The pins sometimes need such a delicate touch it is as if I must only tap the handle of the tuner… and then there’s this exquisite turn of the pin. It is as soft as a breath. Just this and the strings go from sharp or flat to tune.

I paint a gift. Jonathan Byrd answered a question about the colors of Jupiter. The light colors are rising, the darker colors are sinking. I set myself rules, a structure to this painting. The brush strokes of lighter colors go up, darker ones go down as I paint the red spot of Jupiter.

These things are part of a sabbatical I gave myself.

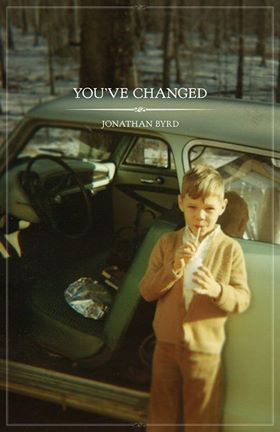

Jonathan and I met again at a poetry reading for his new book, You’ve Changed. We discovered a mutual interest in science, and I asked for his help in editing some of  my poetry. The timing was brilliant. I’d come to the conclusion I had to take a step back and send Seek the Monster to a developmental editor. Here was an opportunity to study more science that appealed to me, and was necessary for future books, as well as study poetry. I could learn from someone who often hides a whole novel of meaning in a few short lines. Just reading Mary Oliver’s A Poetry Handbook was not enough—though I did get it on his recommendation. He has been helping me put my hands to the words from a new direction, my mind to reach for new rhythm.

my poetry. The timing was brilliant. I’d come to the conclusion I had to take a step back and send Seek the Monster to a developmental editor. Here was an opportunity to study more science that appealed to me, and was necessary for future books, as well as study poetry. I could learn from someone who often hides a whole novel of meaning in a few short lines. Just reading Mary Oliver’s A Poetry Handbook was not enough—though I did get it on his recommendation. He has been helping me put my hands to the words from a new direction, my mind to reach for new rhythm.

With our discussions, help on a couple of poems, and ongoing work on one of my long poems, I knew it was coming. Jonathan set a challenge for me: Write a sonnet. He said there was freedom in the structure of a sonnet. He is a musician and poet, and so he understands meter. I find it hard to identify—even when he’s read a poem out loud, emphasizing the iambic pentameter. I listen to the first reading again, or read it myself desperately trying to find it. Challenge me with writing a sonnet? I just shake my head, but I also get to work.

But structure? I could only reach for it with my paint brushes. Look at structure in a different way. I thought about our conversations on dark matter, and gas giants. Light colors rise. Darker ones fall.

Painting isn’t the key means of my study. It just breaks loose some of my fears, opens up my mind to a new way of feeling the poetry.

I also set myself a task of reading sonnets, and on a spin with the Poetry app, I discovered Pablo Neruda wrote sonnets. I love his work, so bought 100 Love Sonnets. It has a side by side Spanish and English. I read out loud:

Neruda, LXVII (Figurehead of a ship)

The girl made of wood didn’t come here on foot;

suddenly there she was on the beach sitting on the cobbles,

her head covered with old sea flowers,

but expression the sadness of roots.

There she stayed, watching over our open lives,

the moving and being and going and coming over the earth,

as the day faded its gradual petals. She watched

over us without seeing us, the girl made of wood:

crowned by ancient waves, she looked out

through her shipwrecked eyes.

She knew we live in a distant net

of time and water and waves and noise and rain

without knowing if we exist, or if we are her dream.

I have read translated works by Robert Bly, whom I’ve seen translate French in meter and meaning. He was set against other translators. One had the meter. Another had the meaning. He had both, which is an astonishing accomplishment. That’s part of the reason I always get the dual language books for poets who do not write in English. I let my Afrikaans lead me, stumbling, through Rilke’s German.

I read Neruda’s sonnets, and was caught by the imagery of the one above. Then I met the: “the moving and being and going…” and I couldn’t hear any kind of real meter with it—at least not the one I was looking for. Using my rusty French, I inferred the Spanish, and read… “el ir y ser y andar y volver por la tierra.”

I can only guess at the meaning, but while I still do not trust I hear any kind of meter… I’m melted, transported. I’m somewhere else. Just the sounds move me far more than the English words. And I know it must be the rhythm, in part.

I go back to the Mary Oliver’s A Poetry Handbook. “The Alphabet—The Family of Sounds”. Vowels and consonants. Consonants become mutes and semivowels, and some semivowels are liquids, and others aspirate. They move words upon the tongue adding something to the meaning, weighting the words or letting them float or fly and go beyond just letters. I see this now.

Reading just the Spanish I cannot quite understand—I see the power in this. It is akin to the sharp and flat notes of my once neglected harp that I am tuning—bringing out music between the taut tension of bowing wooden box and metal pins. It is in the way I am painting, with flowing brushes and mingled colors.

But I still cannot turn my own words into metered rhyme.

I am using these varied things to open up my mind to hearing iambic pentameter. And I read, read, read more sonnets. Listening with ears more open.

The task, for me, isn’t to become someone who writes sonnets. Or metered poems. I’d like to. I hope to. I am working towards that. But it isn’t the goal. Nor is becoming a painter, or a harp player. It is a journey in exploring other sides to language use. Sounds and movement. Jonathan’s challenge and his work on one of my poems have already opened up more ways to edit and revise my fiction.

While I wait for the developmental editor to return my manuscript, I explore a new world of language, and reach for it reading poetry aloud, look for the sounds and rhythm of language, and learn so much as I fall in love with words again.

____

For more information about Jonathan Byrd, please check out his website http://www.jonathanbyrd.com/. Check out his CDs, and his Byrd Word podcasts are quite a lot of fun.